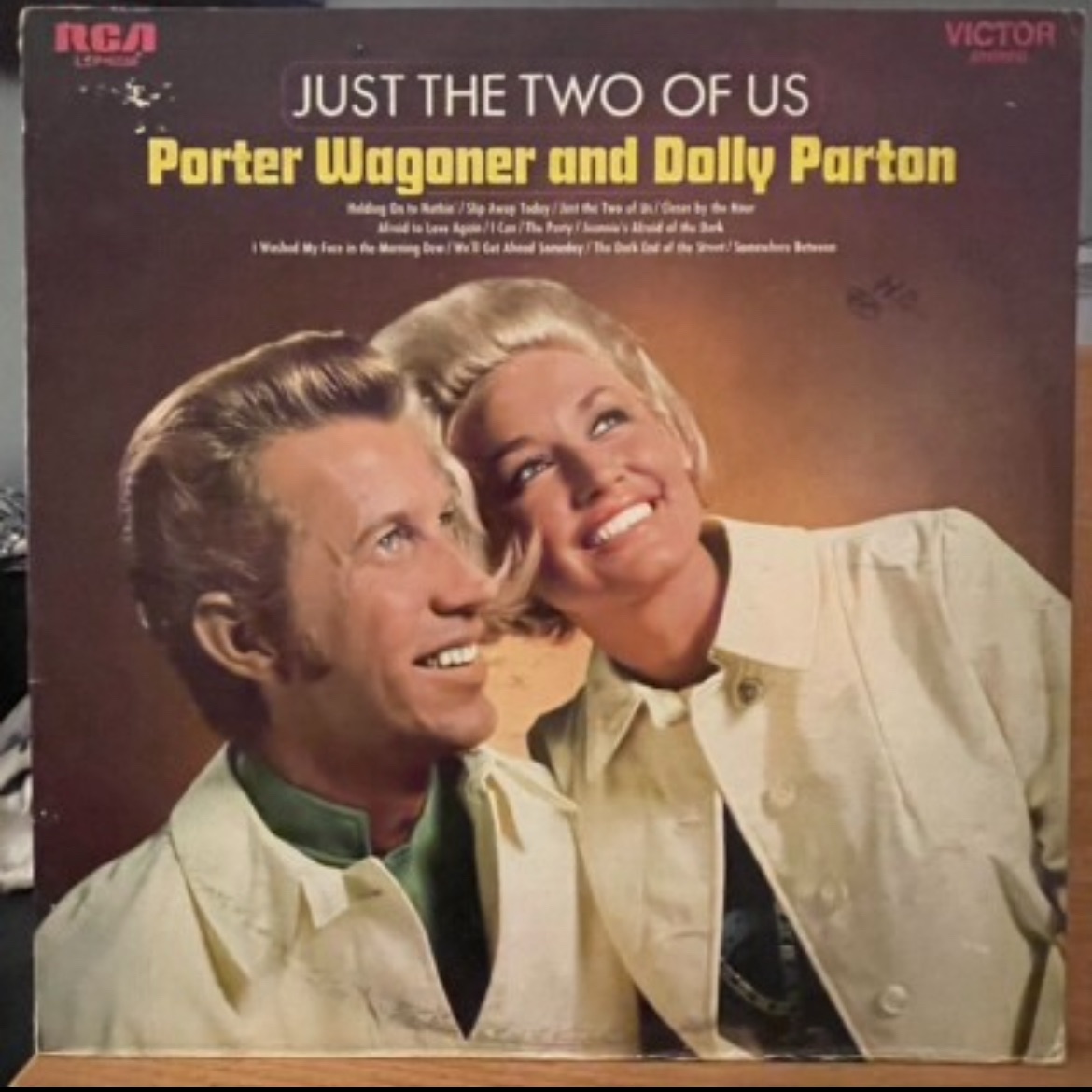

1968: The Start of Porter & Dolly’s Iconic—but Tumultuous—Collaboration

Many more than just the two of them cared when Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton released their second collaborative studio album, Just the Two of Us, on RCA Victor, on this day—September 9—in 1968.

The album solidified that neither their onstage chemistry nor fans’ enthusiasm for the pair was a fluke. Just the Two of Us climbed to No. 5 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart and produced three singles. “Holding on to Nothin’” and “We’ll Get Ahead Someday” both cracked the Top 10 on the Hot Country Songs chart, proving that the duo’s harmonies could thrive on radio as well as television. Though “Jeannie’s Afraid of the Dark” stalled at No. 51, it has endured as one of the most hauntingly poignant entries in their catalog.

The success made Wagoner and Parton one of country music’s most bankable duos, showing that their partnership was more than a TV attraction—it was a musical force. Billboard and Cashbox both praised the record, with particular attention to the pair’s heartfelt performances on “The Dark End of the Street” and “I Washed My Face in the Morning Dew.”

Looking back, critics like Kevin John Coyne from Country Universe noted that “a large part of the appeal of these classic duets is that it feels like you’re eavesdropping on a real couple.” That intimacy—sometimes sweet, sometimes strained—was exactly what made them compelling. And while the collaboration would one day unravel in public fashion, Just the Two of Us remains a testament to the magic they created when their voices blended in harmony.

Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton’s songs were often described as “like eavesdropping.” “The emotional honesty is so raw,” one critic noted.

For Parton, Just the Two of Us was more than a duet album—it was a pivotal stepping stone. Still carving out her own space as a solo artist, she used the partnership to sharpen her songwriting and vocal delivery while laying the foundation for the superstardom that would define her career.

For Wagoner, the record showed a different kind of resilience. By opening his stage and his sound to Parton’s youthful energy, he managed to keep himself relevant in a genre shifting rapidly at the close of the ’60s. Their blend—his seasoned, traditional lean matched with her fresh, emotional edge—cemented them as one of country’s most dynamic duos.

Together, they set the gold standard for male-female collaborations. Their duets balanced storytelling, harmony, and vulnerability in ways that echoed through the work of George Jones and Tammy Wynette, Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn, and later even in powerhouse pairings like Brooks & Dunn with Reba McEntire.

Yet beneath the polished harmony was real tension. That tension—the push and pull of two strong artistic identities—was part of what made their music so gripping. It added an undercurrent of authenticity that fans could feel, even if they couldn’t see the storm clouds forming behind the scenes. Just the Two of Us didn’t just showcase two great voices—it captured the beginning of a partnership as brilliant as it was fragile.

Their Tension Was Palpable

“My husband and I don’t argue, but Porter and I did nothing but fight,” Parton once told W Magazine. “It was a love-hate relationship.”

That push and pull coursed through Just the Two of Us. “Holding on to Nothin’” gave voice to the ache of clinging to a fading relationship. “We’ll Get Ahead Someday” was a working-class anthem that married grit with hope. And “Jeannie’s Afraid of the Dark” showed their willingness to step into hauntingly somber territory. The record wasn’t just a duet album—it was a window into the friction, affection, and contradictions that defined their partnership.

In hindsight, the project foreshadowed their eventual unraveling. By the mid-1970s, Parton was weary of being labeled Wagoner’s “girl singer.” Though she had joined his television show in 1967, her ambitions were growing, her songwriting catalog expanding, and her solo singles like “Joshua” and “Coat of Many Colors” finding success. She was ready to step into her own spotlight.

But Wagoner didn’t want to let her go. Their disagreements turned bitter, and their bond grew increasingly strained. To explain herself, Parton wrote “I Will Always Love You” as both a farewell and a thank-you. She first sang it to him in his office. Wagoner, moved to tears, reportedly told her: “That’s the best song you ever wrote. And you can go—if I can produce that record.”

It was a moment that crystallized their complicated legacy: two artists whose clashes produced as much brilliance as their harmonies.