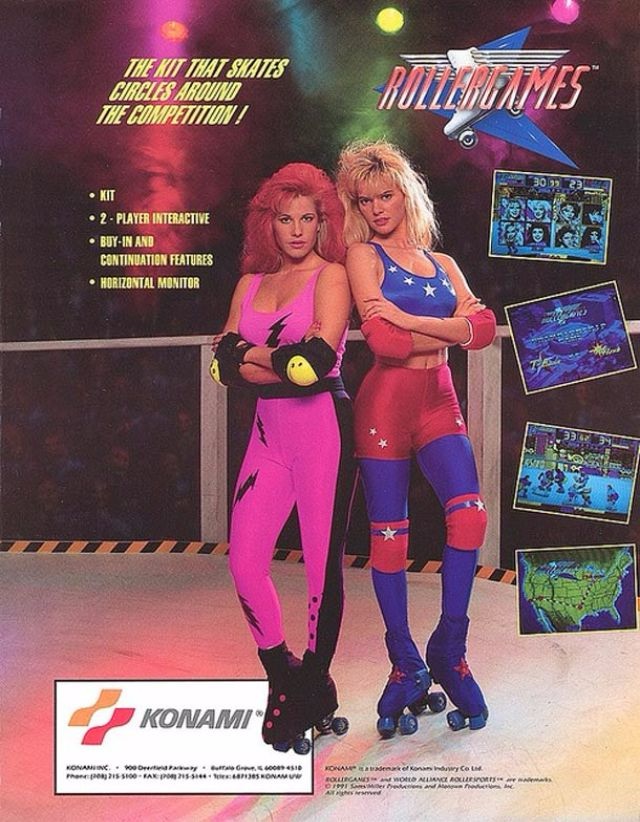

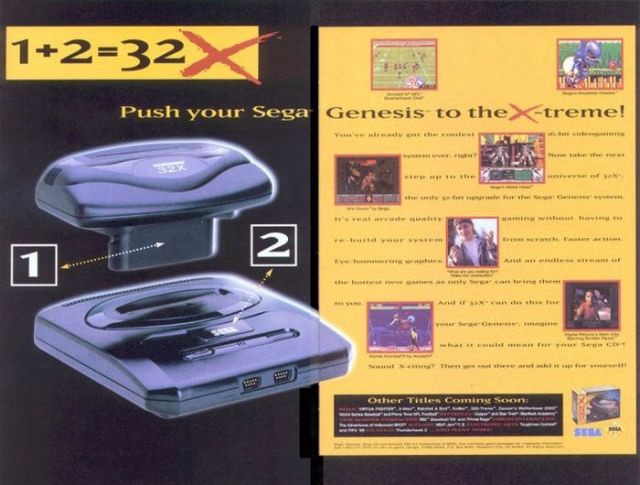

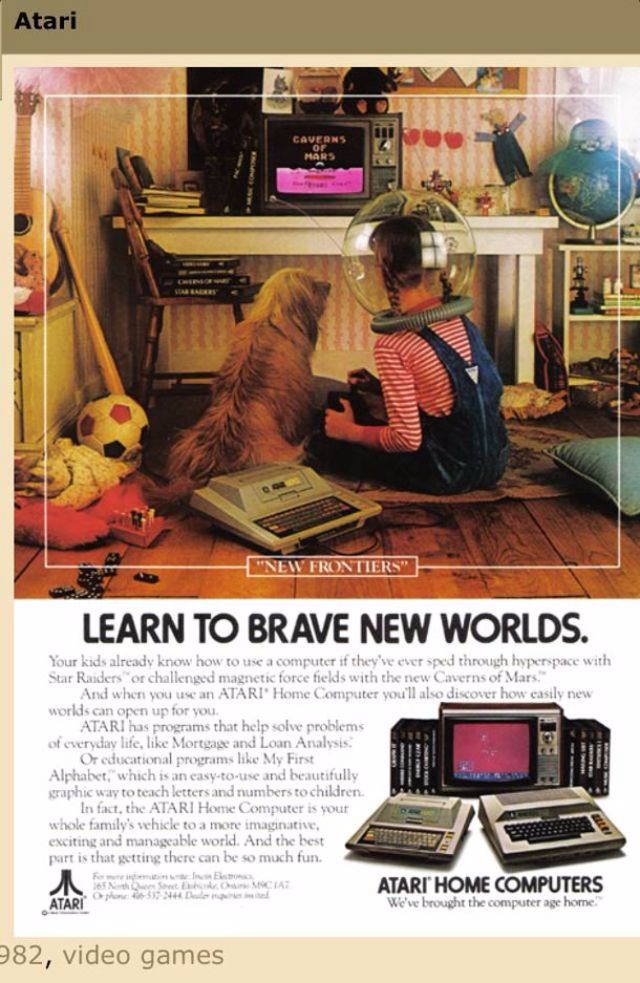

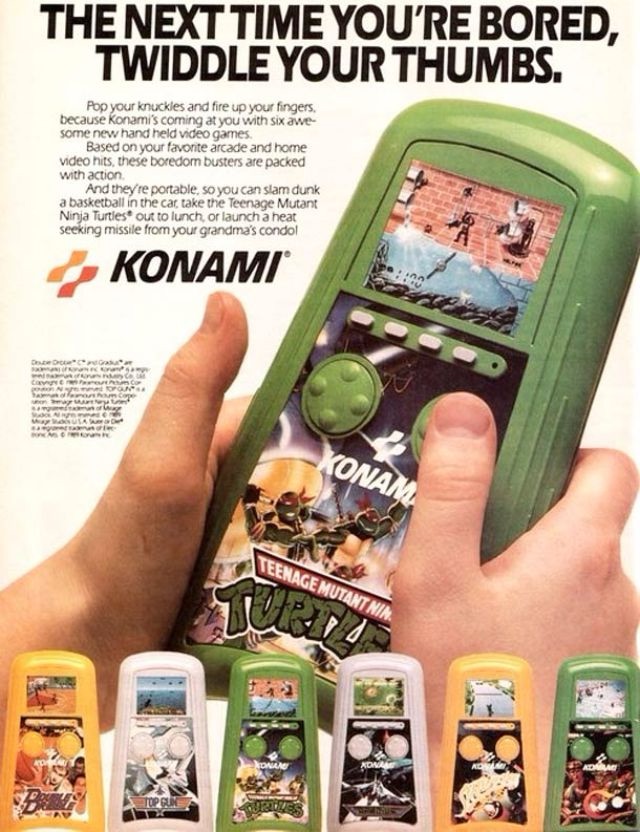

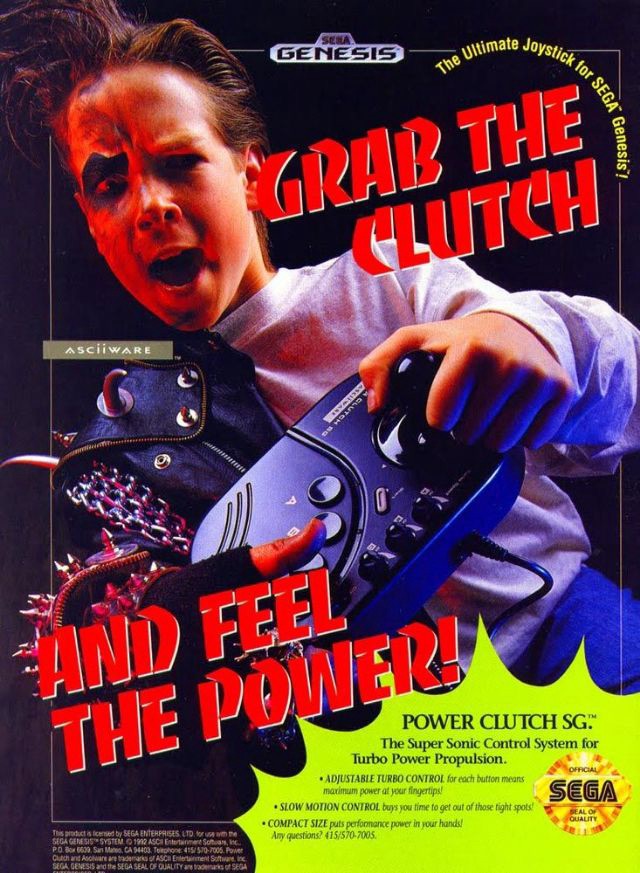

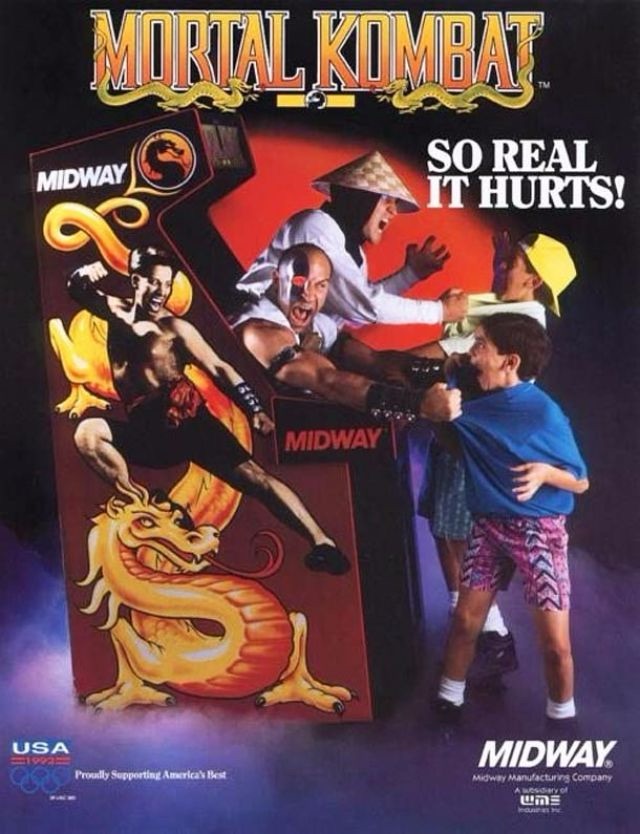

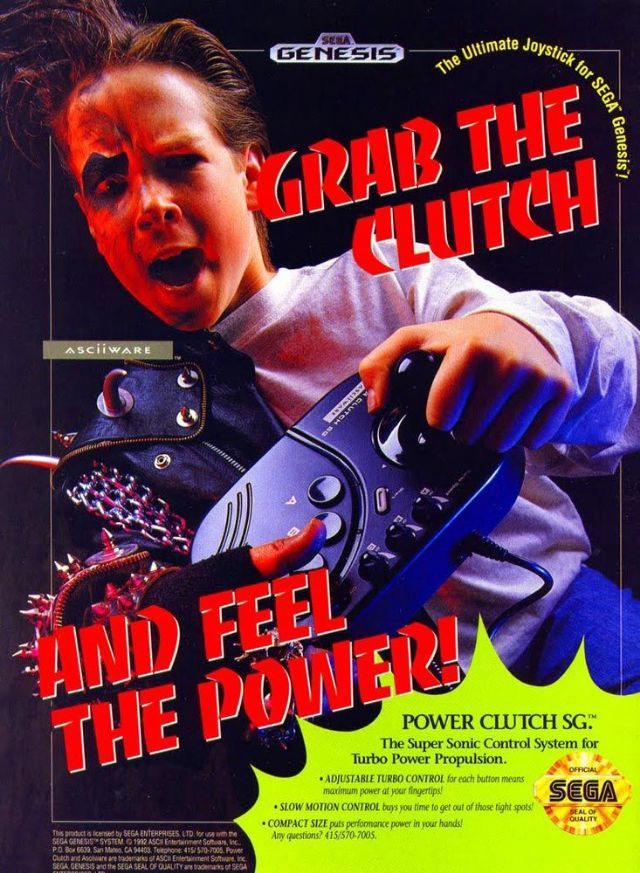

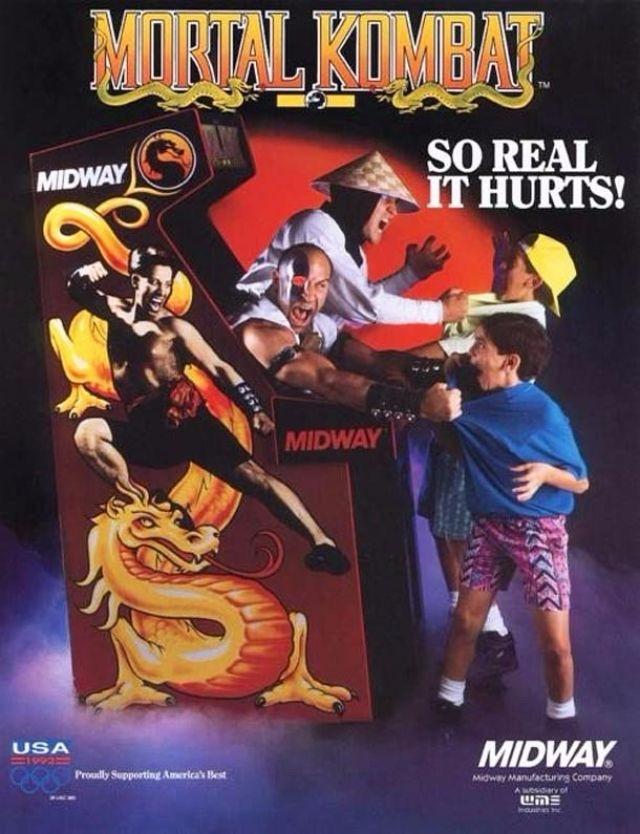

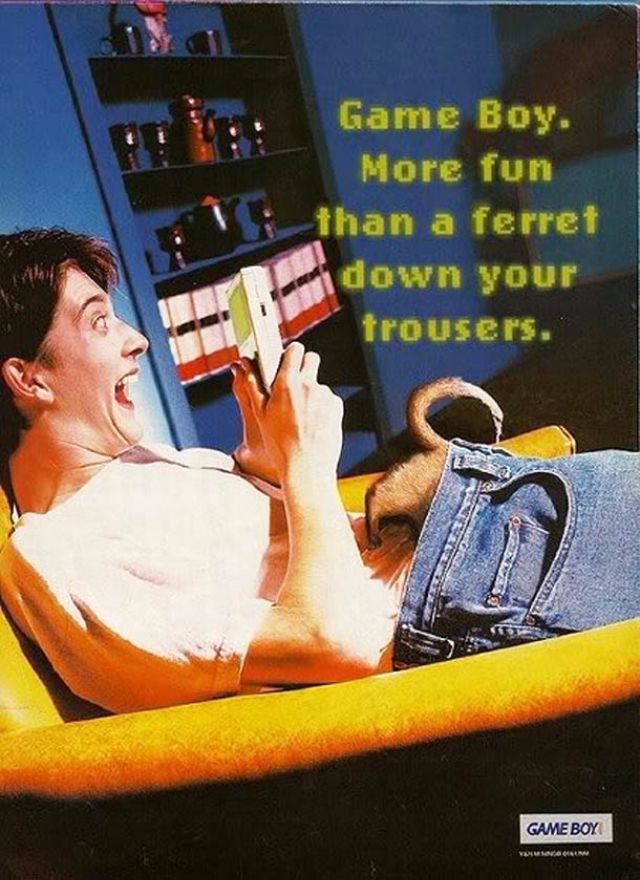

Amazing vintage video game ads from the 1980s and 1990s

This extended photo collection displays memorable old ads that run in gaming magazines in the 1980s and 1990s and show how radically different the video games were advertised 40 years ago.

This was the time when people used to get the gaming news from magazines which were usually a few weeks old by the time a new issue hit shelves.

By looking at these ads, it is clear that many advertisers didn’t really understand how to relate to gamers, especially when the video games market start to mature.

Tech-corp camp, goofiness, and the constant subtext that all video game players are immature teenage boys overflowed from the strange ad spots of the era. The result was a sometimes amazing, sometimes sad, and sometimes downright weird.

The 1980s began amidst a boom in the arcade business with giants like Atari still dominating the market since the late-1970s.

Another, the rising influence of the home computer, and a lack of quality in the games themselves led to an implosion of the video game market that nearly destroyed the industry.

It took home consoles years to recover from the crash, but Nintendo filled in the void with its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), reviving interest in consoles. Up until this point, most investors believed video games to be a fad that has since passed.

In the remaining years of the decade, Sega ignites a console war with Nintendo, developers that had been affected by the crash experimented with the more advanced graphics of the PC, and Nintendo released the Game Boy, which would become the best-selling handheld gaming device for the next two decades.

In the early-1980s, arcade games were a vibrant industry. The arcade video game industry in the US alone was generating $5 billion of revenue annually in 1981 and the number of arcades doubled between 1980 and 1982.

The effect video games had on society expanded to other mediums as well such as major films and music. In 1982, “Pac-Man Fever” charted on the Billboard Hot 100 charts and Tron became a cult classic.

Following a dispute over recognition and royalties, several of Atari’s key programmers split and founded their own company Activision in late 1979.

Activision was the first third-party developer for the Atari 2600. Atari sued Activision for copyright infringement and theft of trade secrets in 1980, but the two parties settled on fixed royalty rates and a legitimizing process for third parties to develop games on hardware.

In the aftermath of the lawsuit, an oversaturated market resulted in companies that had never had an interest in video games before beginning to work on their own promotional games; brands like Purina Dog Food.

The market was also flooded with too many consoles and too many poor quality games, elements that would contribute to the collapse of the entire video game industry in 1983.

By 1983, the video game bubble created during the golden age had burst and several major companies that produced computers and consoles had gone into bankruptcy.

Atari reported a $536 million loss in 1983. Some entertainment experts and investors lost confidence in the medium and believed it was a passing fad.

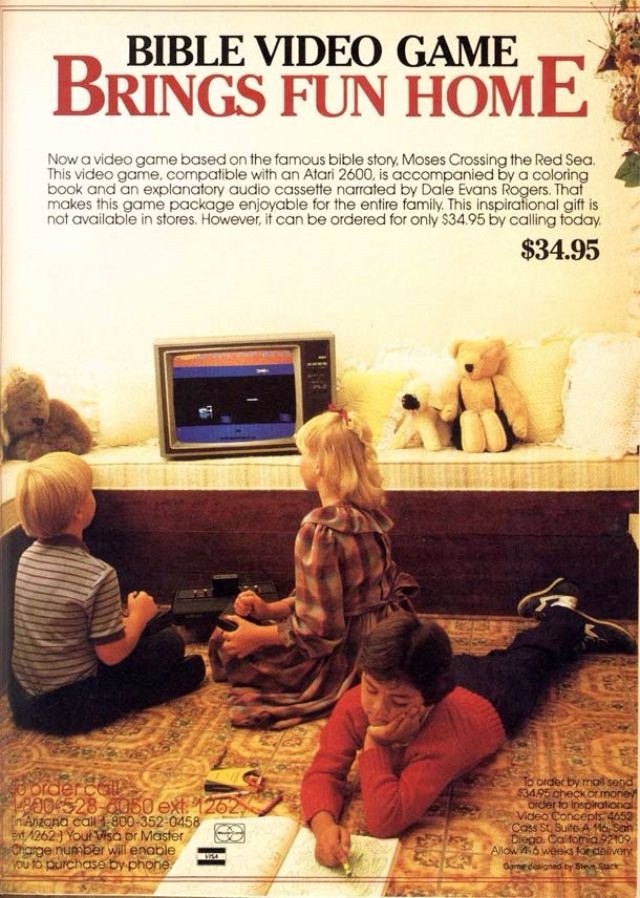

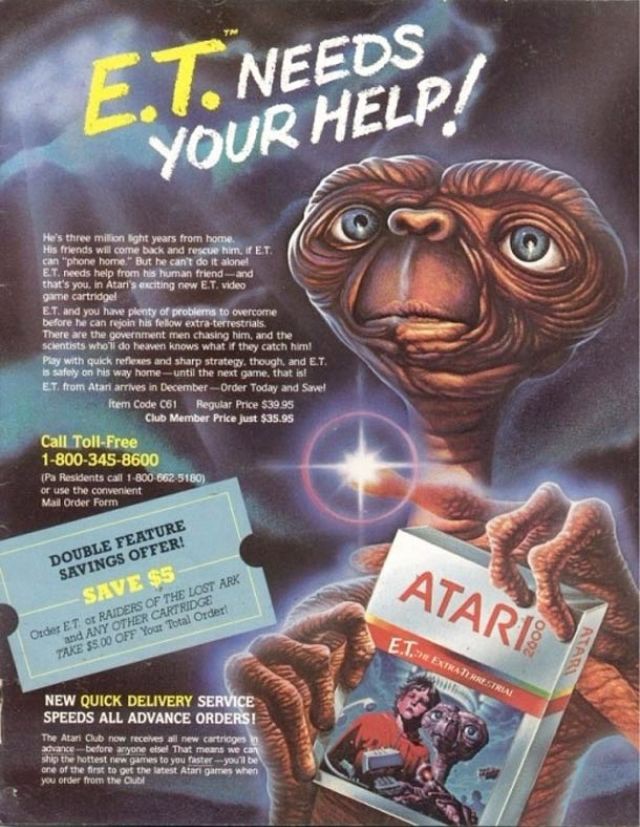

A game often given poster child status to this era, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial had such bad sale figures that the remaining unsold cartridges were buried in the deserts of New Mexico.

The brunt of the crash was felt mainly across the home console market. Home computer gaming continued to thrive in this time period, especially with lower-cost machines such as the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum.

Some computer companies adopted aggressive advertising strategies to compete with gaming consoles and to promote their educational appeal to parents as well.

Home computers also allowed motivated users to develop their own games, and many notable titles were created this way, such as Jordan Mechner’s Karateka, which he wrote on an Apple II while in college.

In the late 1980s, IBM PC compatibles became popular as gaming devices, with more memory and higher resolutions than consoles, but lacking in the custom hardware that allowed the slower console systems to create smooth visuals

By 1985, the home market console in North America had been dormant for nearly two years. Elsewhere, video games continued to be a staple of innovation and development.

After seeing impressive numbers from its Famicom system in Japan, Nintendo decided to jump into the North American market by releasing the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES for short.

After release, it took several years to build up momentum, but despite the pessimism of critics, it became a success. Nintendo is credited with reviving the home console market.

One innovation that led to Nintendo’s success was its ability to tell stories on an inexpensive home console; something that was more common for home computer games, but had only been seen on consoles in a limited fashion.

Nintendo also took measures to prevent another crash by requiring third-party developers to adhere to regulations and standards, something that has existed on major consoles since then.

One requirement was a “lock and key” system to prevent reverse engineering. It also forced third parties to pay in full for their cartridges before release, so that in case of a flop, the liability will be on the developer and not the provider.