From Taboo to Trend: Women Who Challenged Beauty Norms with Armpit Hair

For over a century, women have been told what their bodies should look like—and just as importantly, what they shouldn’t.

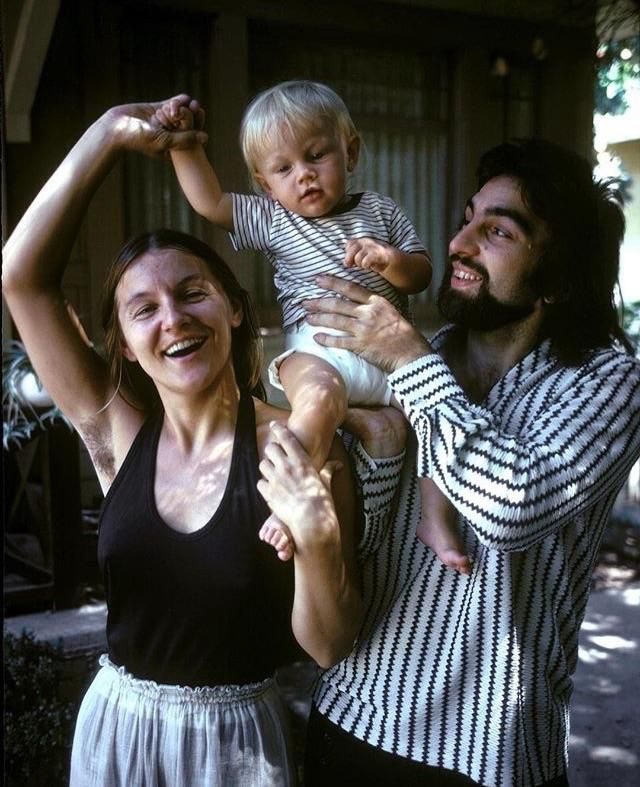

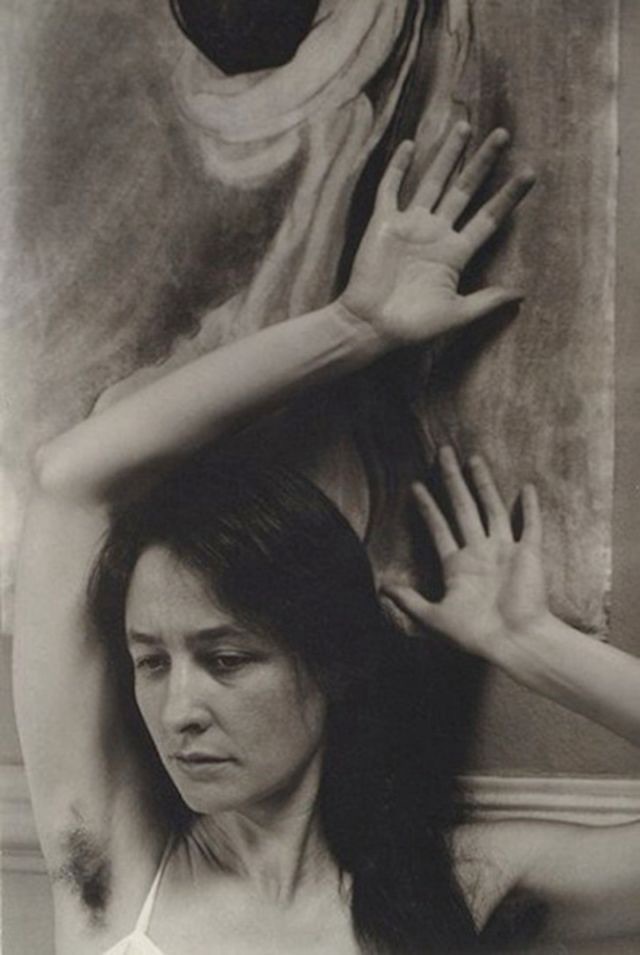

Among the most persistent expectations has been the removal of body hair. While many women still follow this unwritten rule, others have chosen to ignore it altogether, embracing their natural appearance without apology.

That simple act of defiance has, at times, become a quiet but powerful form of rebellion—especially when embraced by some of the world’s most visible public figures.

In the early 20th century, the idea of women shaving their bodies was far from common. A market for female hair removal simply didn’t exist in the United States at the time—it had to be created from scratch.

Researcher Christine Hope Hansen notes: “The practice of removing hair from the underarms and legs was practically unheard of. In fact, hair removal was such a novel concept when it was first introduced that companies had to persuade women of the benefits, and demonstrate how to practice it.”

The turning point came in 1915, when Gillette released the first razor designed specifically for women. By capitalizing on shifting fashion trends—sleeveless dresses and shorter hemlines—razor and depilatory companies cleverly framed body hair as a “problem” that needed solving.

Advertising campaigns were subtle yet relentless, carefully aligning beauty with smooth, hairless skin. From the mid-1910s through the 1930s, dozens of brands echoed this message, planting the seeds of a standard that still lingers today.

Early ads promoting underarm hair removal appeared as early as 1908, but they grew far more frequent after 1914. One striking example was a 1915 Harper’s Bazaar ad for a depilatory powder called X Bazin. It featured a woman in a sleeveless gown lifting her arm with confidence, paired with the caption: “Summer Dress and Modern Dancing combine to make necessary the removal of objectionable hair.”

The message was unmistakable—body hair had no place in the life of a “modern” woman.

To make grooming sound less harsh, advertisers avoided words like shaving and legs. Instead, they used more refined language: “smoothing” instead of shaving, and “limbs” instead of legs. These weren’t just ads selling beauty products—they were lessons teaching an entirely new standard of femininity.

By the 1920s, underarm hair was openly described in ads as “objectionable,” “unsightly,” and “unclean.” Removing it, meanwhile, was framed as the mark of modesty, refinement, and even moral superiority. Hair-free skin wasn’t just about hygiene—it was about being “dainty,” “elegant,” and “perfectly groomed.”

Over time, this manufactured norm became deeply ingrained. Today, more than a century later, the overwhelming majority of American women—estimated at 80 to 99 percent—still regularly remove body hair.

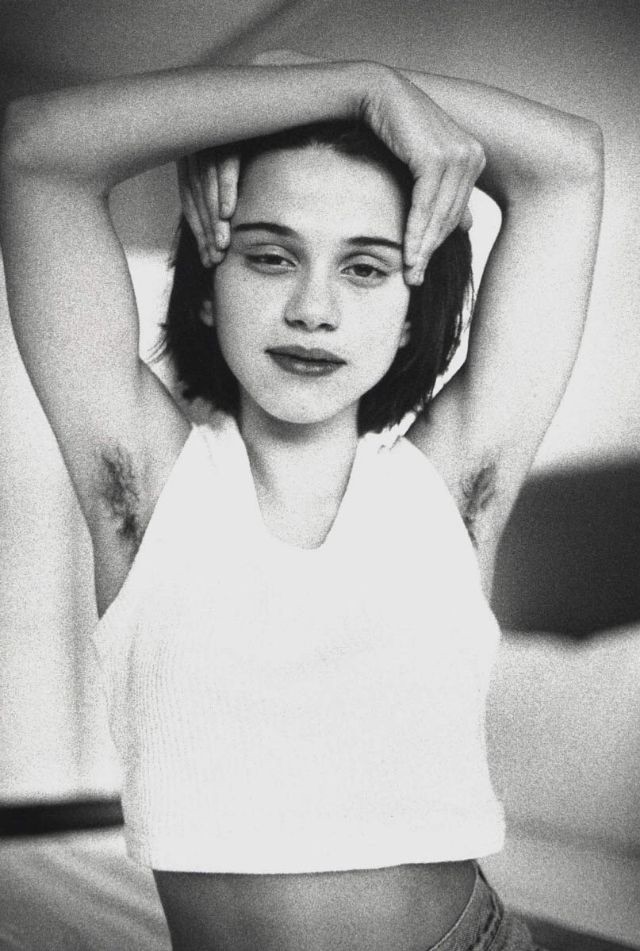

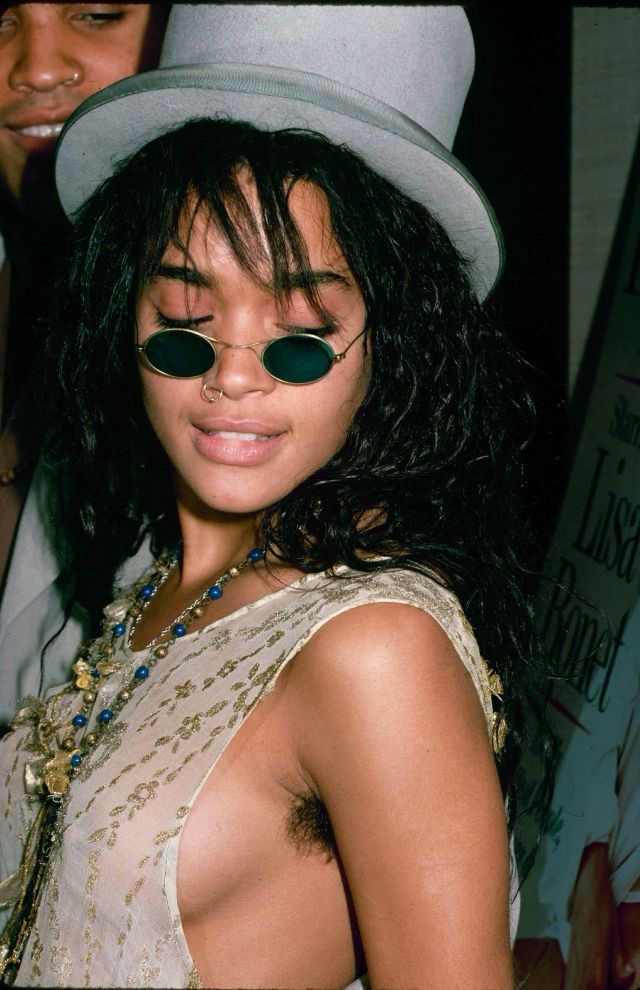

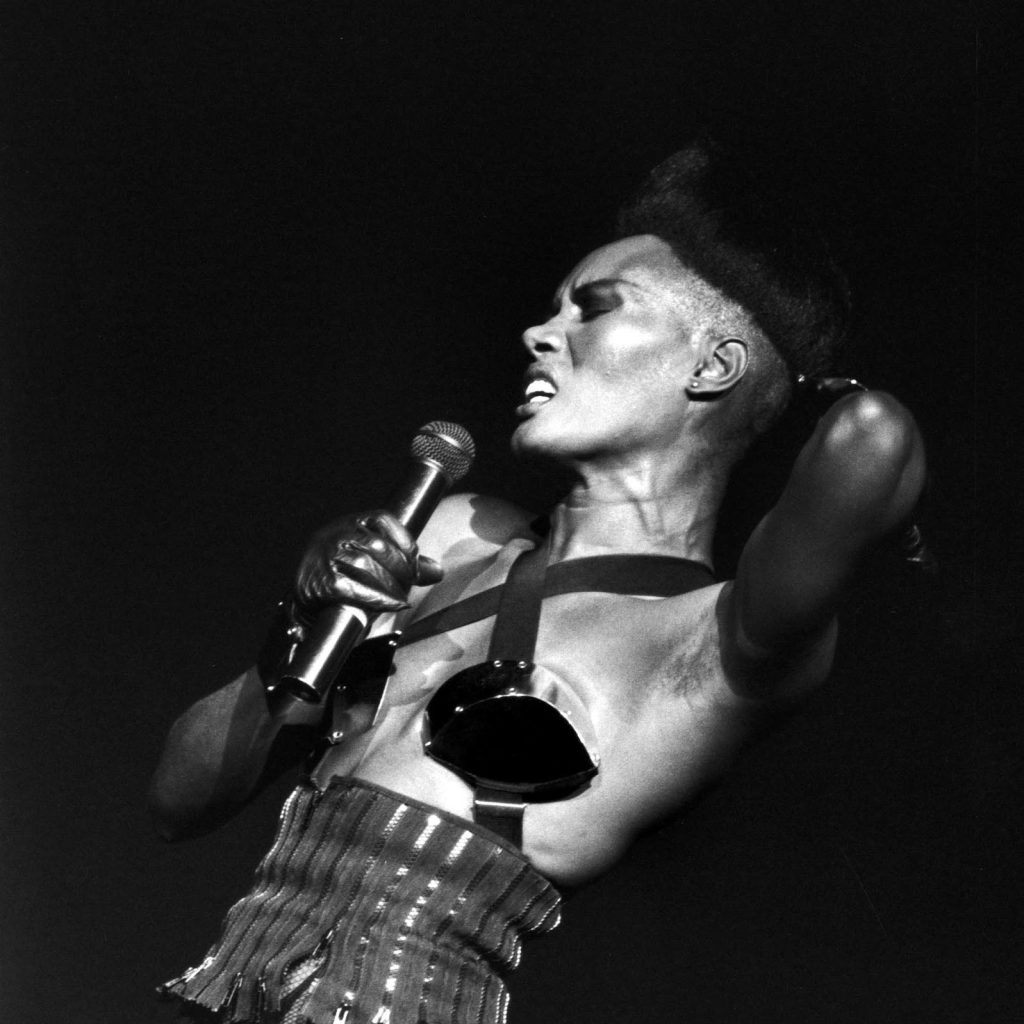

And yet, choosing not to shave remains a bold statement. It challenges a century of cultural conditioning and redefines beauty on one’s own terms. That defiance has become particularly visible in pop culture whenever celebrities embraced it.

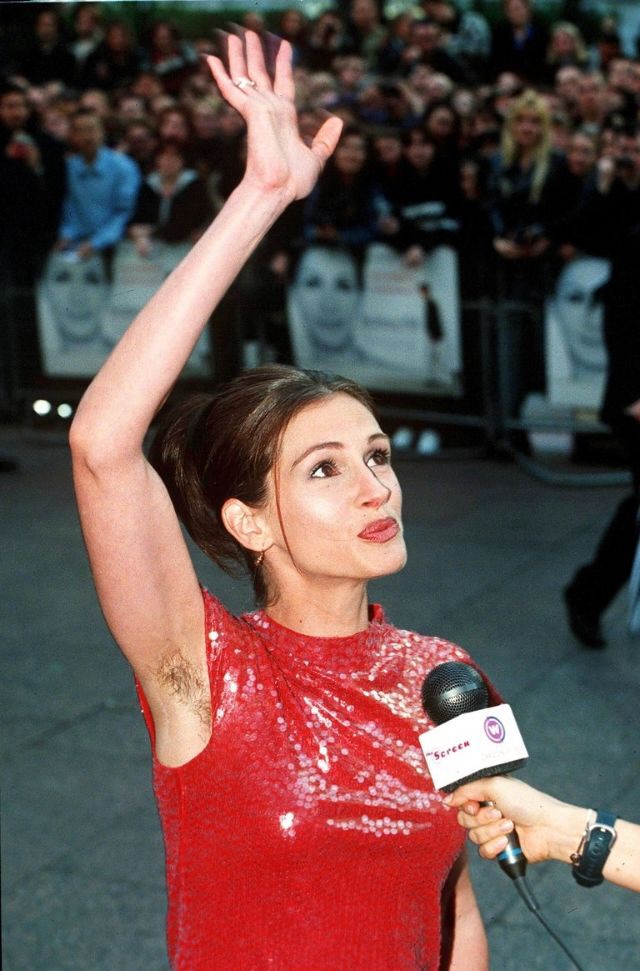

One of the most famous examples came in 1999, when actress Julia Roberts appeared at the Notting Hill premiere with unshaven underarms. The sight of natural body hair—something completely ordinary—sparked a media frenzy. Headlines weren’t focused on her performance or her red-carpet look, but on the simple fact that she hadn’t removed her body hair.

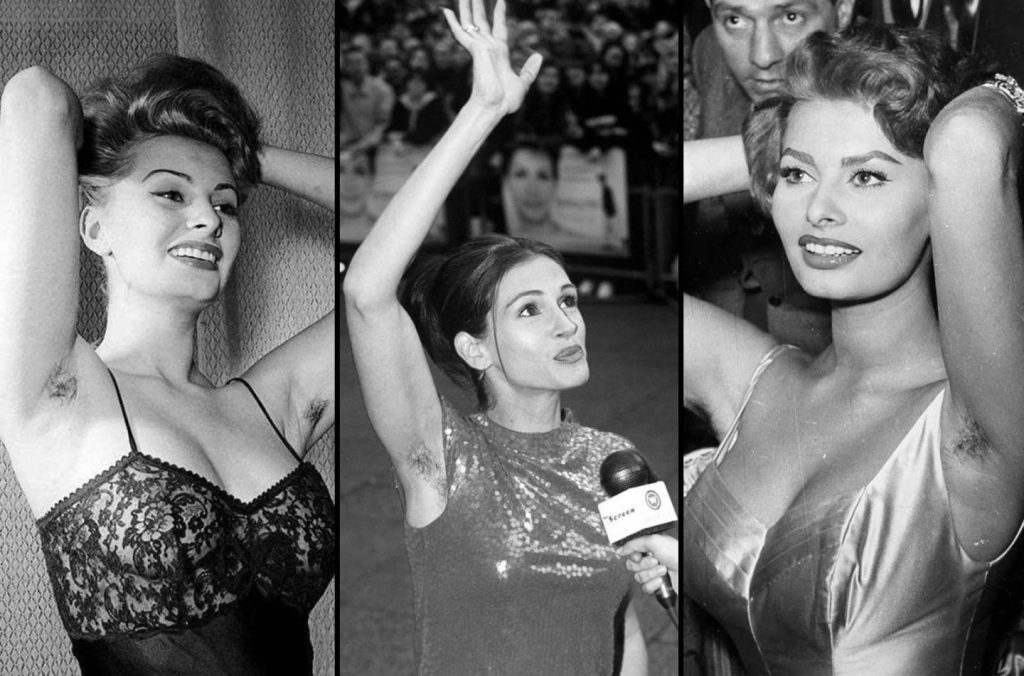

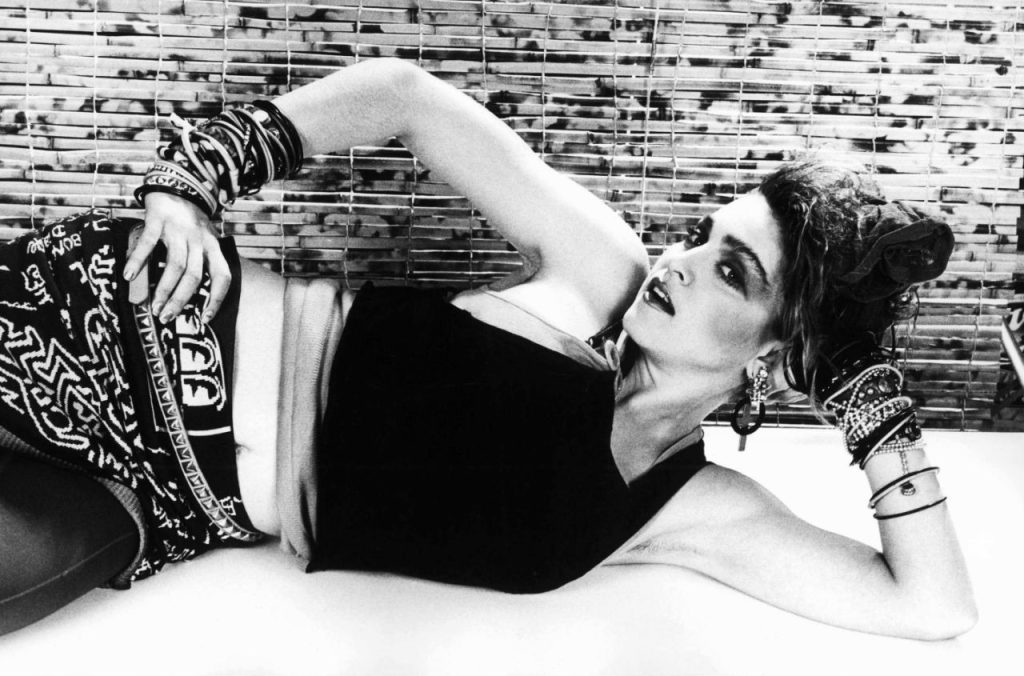

She wasn’t the first, nor the last. From Sophia Loren in the 1960s to Madonna in the 1980s and countless stars today, each moment of visibility has chipped away at the taboo. For some, it’s an unapologetic embrace of their natural selves. For others, it’s an intentional act of protest against rigid, manufactured beauty standards.

What remains clear is this: body hair, once weaponized by advertisers to sell razors and powders, has become more than a matter of grooming. For many women, it’s a statement—whether of rebellion, individuality, or simply comfort in their own skin.